Hallmark as Hero

Sophia Tobin, Goldsmiths' Company Deputy Librarian, recounts the enduring necessity and appeal of the hallmark

In the Goldsmiths’ Company’s library, we see a lot of heirlooms. Images of brooches, spoons and soup tureens wing their way to us with the question ‘can you tell me the story of this?’. It isn’t always within our power to tell those enquirers exactly what they want to know - how their grandparents met, for example. But, if we have a clear hallmark, we can tell where and when a piece was marked; who made it or brought it for hallmarking; and what fineness of metal it is. This slightly different story might not be romantic, but it is important, with its roots far back in a time of chivalry. It is a story of justice and protection which has endured through many challenges, including the disruptions of today’s world.

It begins in 1300, with a heraldic symbol from a knight’s shield. When Edward I decreed that trusted goldsmiths, or ‘Guardians of the craft’ be sent out to shops to assay precious metal and ensure it was of the correct purity, he also decreed that silver and gold of the correct standard be marked with the ‘King’s mark’. This was taken directly from the royal coat of arms, part of the lion passant guardant that would have been seen on his shield, and which we refer to colloquially as the leopard’s head; today’s London town mark is descended directly from that first stamp of quality.

The establishment of the King’s mark was recognition of the importance of the quality of gold and silver. A medieval customer going into one of the goldsmiths’ shops on Cheapside needed to know that if they bought a piece of silver, whether spoon or rosewater dish, it was sterling – 92.5%. This thing of beauty was not just that: it was also portable money. As the years passed, further elements of traceability were added: in 1363 the maker’s mark – now known as the sponsor’s mark, and in 1478 the date letter. That year, it became the responsibility of goldsmiths to bring their pieces to be tested at the newly-created Assay Office, in Goldsmiths’ Hall, a process which continues there five centuries later.

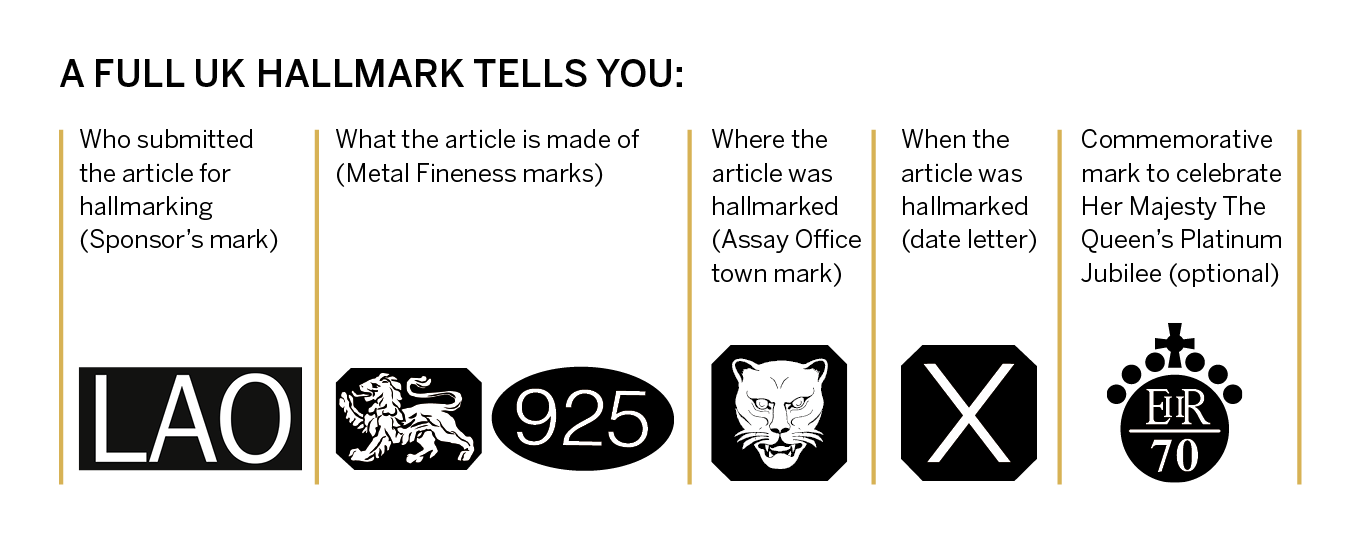

Over time, the hallmark has evolved. Elements have been added and taken away; the leopard’s head has been leonine, crowned, uncrowned and briefly, displaced by Britannia. But the purpose of the hallmark has remained the same. The current hallmark consists of: the town mark (indicating which Assay Office has marked the piece); fineness mark; sponsor’s mark (previously known as the maker’s mark) and date letter, now optional but still standard. On the Antiques Roadshow, pieces are held up to the light, the marks explained and identified. But it hasn’t always been like this; for many years, hallmarks were obscure and little understood.

The earliest makers’ marks were pictograms rather than initials, symbols indicating the name of the maker. At the time, literacy was not universal, and symbols were part of the culture of everyday life, from those knights’ shields I mentioned to shop signs. But our only barrier to understanding these marks is not just having to switch to a medieval state of mind. All of the earliest records of makers’ marks for the London Assay Office were destroyed by a fire in 1681, proving that furnaces and written records are an unhappy combination.

Our earliest surviving record is a metal plate of makers’ mark impressions, created in 1682 after the fire, but the record of the names which went with this plate this has been lost. Silver scholar John Culme deciphered one of the most prominent of these makers – the mark had been referred to as the ‘goose in the dotted circle’ for years until his research revealed that it had belonged to a silversmith called John Duck. Occasionally we show this mark to schoolchildren. ‘What do you think that bird is?’ we ask, hopefully, waiting for them to identify the goose so we can surprise them. ‘A DUCK!’ they shout, with unwavering certainty. Luckily many of the mysteries of the plate have now been revealed. Dr David Mitchell took on the task of deciphering the names over a 15-year period – his scholarship is now available in his book Silversmiths in Elizabethan and Stuart London: their lives and their marks.

Even once initials had been introduced into makers’ marks, for many centuries hallmarks were only understood by a small group of people: the trade and Assay Offices. Consumers vaguely understood that the hallmark was a guarantee, but there was no real sense of what the symbols meant.

The information was unlocked by eccentric antiquarian, Octavius Morgan, in the early 1850s; he was the first person to publish the sequence of date letters from the London Assay Office. He was followed by Wilfred J. Cripps and William Chaffers, respectively, the latter incurring the wrath of the Goldsmiths’ Company when he published rather too much information without gaining permission. These early hallmarking works established the precedent for the many rich and valuable hallmarking publications that followed.

Detail of Maria Corbet Cup probably by Noe Jeopart, 1587/8. (The Goldsmiths’ Company. Image: Richard Valencia)

Even today, understanding hallmarks can take some research. The ‘Make Your Mark’ competition asks makers to incorporate the London hallmark into their design. Caitlin Murphy, one of two gold winners in the 2021 competition, incorporated a different element of the hallmark into each shot glass in her piece Punch Drunk. ‘It was really only when I started researching the hallmark itself that I understood all the individual components and what they stand for – and that’s what really excited me.’ Fellow gold winner Isabella Kelley, who based her work Celebration Whiskey and Olive Set on the tools hallmarkers use, also had to research the details of hallmarks, ‘as I was working primarily in non-precious metals and other materials, I had limited first-hand experience of hallmarks.’

It is not just lack of understanding that has dogged hallmarking. From the beginning, there has been a battle against those who wished to subvert the law, whether by faking hallmarks, cutting out marks and inserting them into other work, dodging duty, or even clipping edges of coins to use the silver (leading to a change in the standard for plate to 95.84 % pure silver in 1697-1720). Opening up the hallmark and its meaning has great advantages, but knowledge is power. In 1822, the leopard’s head mark lost its crown and the sterling lion was changed, without public announcement, in the hope of catching out forgers. Those who administer hallmarks must balance openness with a certain amount of ducking and weaving to defeat the forgers.

Hallmarks on beaker 1667, Goldsmiths' Company Collection

There is another barrier too: dislike. Goldsmiths and silversmiths have not always loved hallmarking. Like all relationships, there have been some bumpy moments, from those who refused entry to their workshops in the early days of hallmarking, to silversmiths who claimed pieces could be damaged by hallmarking. In 1785 the duty draw-back mark, introduced to indicate that duty had been reclaimed after export, had to be withdrawn swiftly after complaints that it had caused damage to finished pieces.

Silversmith Gareth Harris, of Smith & Harris, and member of the Antique Plate Committee, a group of experts who meet at Goldsmiths’ Hall to adjudicate hallmarks, has seen two cycles of the alphabet pass during his time at the bench. ‘Like the changing of the seasons, the yearly change of date letter is a marker of time, and it is always pleasurable to see a new one.’ But even he admits that hallmarking hasn’t always been popular. ‘In a busy workshop, under pressure of deadlines, and with financial constraints, they can be seen as a bureaucratic annoyance….. but in time most smiths come to realise that the guarantee the hallmark adds is worth more to the job than the inconvenience.’ He adds that it can be a positive experience: ‘once the skills of setting struck marks are mastered, their addition comes at an enjoyable point in manufacture, when the making is complete, and the finishing starts.’

Historic date letter

The last fifty years have certainly seen a shift in the maker/hallmark relationship, from tolerance to affection. These days marks can be applied in all manner of ways: still by hand, yes, but also by press or with the delicacy of the laser beam, to a variety of sizes and depths. Robert Organ, Deputy Warden of the London Assay Office, notes that the hallmark is now more than just a guarantee. ‘Large display hallmarks have become part of the design of articles. The sponsor’s mark can signify a brand which is a powerful marketing tool.’ Commemorative marks such as jubilee marks, struck in addition to the normal hallmark, can also be used to add value when selling. Organ adds that one of the great successes of hallmarking ‘is the perception of quality that it gives an article…palladium had been known as a metal able to create jewellery items since the 1950s. However, sales increased markedly when palladium articles needed hallmarking from 2010.’

Caitlin Murphy chose a spaced display mark for her ‘Make Your Mark’ piece. ‘I knew I wanted the hallmark to be visible and for it to add an aesthetic beauty to the overall finish of the piece’. Fellow gold winner Isabella Kelley ‘will definitely consider using hallmarks to a more decorative effect on physical work in the future - participating in the brief has opened a new branch of my designs that I am keen to explore’, and she adds that she likes the ‘refinement’ a hallmark adds to her work.

The term ‘maker’s mark’ was changed to ‘sponsor’s mark’ to show that the mark isn’t always an indicator of the maker. It indicates the person or company who has brought the piece to be assayed – for example, this might be a firm’s mark, when a piece is the product of many hands. But, interestingly, modern craftsmen often cherish their own sponsor’s mark as something uniquely personal to them. Toby Vernon from The Ouze, who regularly creates jewellery that incorporates outward-facing hallmarks, was fascinated by hallmarks even before he became a jeweller. Having sought out vintage pieces with external hallmarks, he uses them in his own work. For Toby, the hallmark is not just about quality, and reflects a very personal sense that he has created the piece. ‘My jewellery celebrates craftsmanship and the hand made. I believe that leaving evidence of the human hand is something to be celebrated in this time of machine-made, highly polished and mass-produced objects…why would you conceal a hallmark? It is part of the process of jewellery making, it shows a maker’s mark like a signature on a painting.’

Whilst some barriers have come down, today’s world has brought new challenges for the hallmark and its mission. The era of fake news is also the era of fake jewellery. A consumer survey at the end of 2019 revealed that a third of so-called ‘gold’ jewellery sold online is not hallmarked, and therefore may be fake. With the increase in internet shopping during the pandemic, this number may well have increased. Despite this difficulty, Robert Organ is far from pessimistic. ‘Hallmarking is as important as ever now. Its popularity is also increasing globally: India has introduced compulsory hallmarking and there is more and more interest from countries in joining the Hallmarking Convention.’

The hallmark might be an unlikely hero. But it has quietly ensured consumer protection over the last seven centuries and continues to do so today. In these uncertain times, if a piece you wear bears an official hallmark, you can count on it: it is real. Through fire, fakery and many other challenges, this earliest form of consumer protection has endured. As the makers of today recognise, it is a thing of beauty in its own right.

Cara Murphy, Lackagh Bowl, Platinum Jubilee Mark